Kimble [Kimball] Bent An Unusual European Who Deserted The British Army And Joined The Hau Hau #21

McDonnell's column, the stronger one, was in the meantime fighting its way out through the forest to the Wai-ngongoro, hard beset by the Hauhaus, who had by this time been reinforced by others from the nearest villages.

The Maoris followed closely in the rear and kept up a heavy fire, to which McDonnell and his officers and men could only return occasionally, their ammunition was getting very short.

With McDonnell marched a French Roman Catholic priest, Father Jean Baptiste Rolland, the padre of the forces,

who had been described only a few weeks before, in a letter written by von Tempsky, as “a man without fear.

” Whenever a soldier fell, whether he was Catholic or Protestant, the kind-faced father was by his side in a moment, tending his wounds, and, if dying, soothing his last moments with a prayer.

He took his turn, too, at carrying the wounded.

Three holes, drilled by Hauhau bullets, ornamented the padre's old wide-brimmed soft felt hat when he reached the Waihi camp that night.

It was just dark when the snoring Wai-ngongoro was reached, and the bridgeless river, running high and swiftly, was forded with some difficulty under fire.

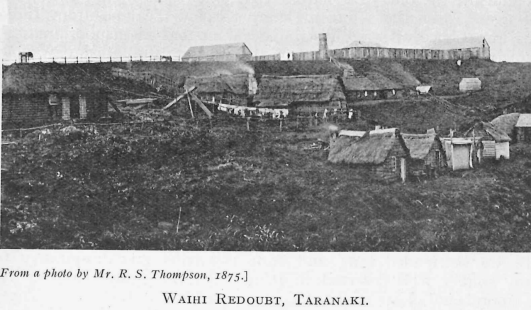

At ten o'clock at night, the redoubt was reached, and here it was found that a mixed party of fugitives from the battle-field, numbering about eighty Europeans besides the Kupapas, had already arrived, and had reported all the officers, McDonnell included, killed or wounded and left on the field.

And how fared Captain Roberts' little rear-guard of sixty men?

Extending his force in skirmishing order, the young officer pushed on as well as he could, carrying his wounded, one in every six.

When darkness came on he halted, for it was hopeless to try to force a way through the jungle-matted woods in the blackness of the night.

It was a cold frosty night, and the wounded were in agonies of pain, which their distressed comrades were helpless to relieve.

There on the damp and freezing ground, they crouched till the moon rose at two o'clock in the morning.

Now, guided by five brave fellows of the Maori contingent, Whanganui and Ngati-Apa men, who stood by Roberts and his wounded to the last, the rear-guard recommenced the retreat.

Struggling wearily on through the tangling kareao and the densely growing shrubs, stumbling over logs and splashing through little watercourses, they emerged at last thankfully on to the open country, and soon, bearing their wounded and dying comrades across the dark flooded Wai-ngongoro, were greeted by the joyful cheers of their comrades, European and Maori, under Kepa te Rangihiwinui, [Captain Kemp] who had set out from the Waihi Redoubt to their rescue when daylight broke.

Only then was the full story of the repulse pieced together, a story of a fight that in point of numbers was only a skirmish, as battles go, but that was the most serious setback the white man had yet suffered at the hands of the brown warriors of the Taranaki bush.

Of the twenty-four whites killed five were officers, men who could badly be spared in that frontier warfare.

The wounded numbered twenty-six, whose rescue from the tomahawks of the Hauhau was carried out in a way truly heroic.

On the morning after the battle, Kimble Bent and his companions, who had been informed by a messenger the previous night of the result of the forest engagement, hurried back to the stockade.

The news of the repulse of the white troops had spread with incredible swiftness all over the Maori country-side, and the Hauhaus from the neighbouring villages gathered in Te Ngutu-o-te-Manu to hear the story of the fight and to share in the distribution of the loot taken on the battle-field.

The village was crowded with Hauhaus, all in a fearful state of excitement, a delirium of triumphant savagery.

Yelling like furies, shouting ferocious battle-songs, waving their weapons in the air, the victorious warriors were there with their spoils, carbines, swords, revolvers, soldiers' caps and belts.

More frightful still was the sight of which Bent had just a glimpse as he entered the gateway of the pa.

Laid out in a low row in the centre of the marae, side by side, were bodies of many white soldiers, nearly twenty of them, all stripped naked, the fallen heroes of Te Ngutu-o-te-Manu.

Just a glimpse the white man had as he entered the blood-stained square.

The next moment he was surrounded by a howling mob of Hauhaus, grinning, yelling, laughing fiendishly, shaking their weapons in his face, all in sheer hate and contempt of anything with a white skin.

Two or three of the Tekau-ma-rua men whom Bent knew came bounding up.

One of them said to him,

“Tu-nui, you must come with me.

It is Titoko's command.”

The Maori led Bent to a small thatched hut on one side of the marae.

Here he shut the white man in and fastened the low sliding-door on the outside.

For a little while the white man sat in the gloom of the windowless whare, listening to the demoniac shouts of the Hauhaus outside, and wondering what would come next, whether, indeed, his own body would not soon be added to the terrible pile of slain soldiers on the marae.

At last, hearing Titokowaru's great voice raised in commanding tones, Bent's mingled curiosity and what was going on.

Discovering a small crack in the reed-thatched walls of the hut, he enlarged it sufficiently to gain a good view of the assemblage on the village square.

There they squatted, men, women, and children, their faces smudged with charcoal or with red ochre, the paint of the war-path.

They were seated on the ground in a great half-circle, facing the staring white corpses of the slain pakehas.

The frightful clamour of the savages had given place with strange suddenness to a dead silence, as they listened to their war-chief's harangue, and watched him pacing quickly to and fro, with his sacred taiaha in his hand, now carrying it at the trail in the taki attitude, now dandling it high in the air as he intoned a chant to his battle-god Uenuku.

“Bring out my pakeha Tu-nui-a-moa!” cried Titokowaru, when he had ended his speech.

A Maori rose, and, unfastening the wharé door, led Bent out on to the assembly-ground.

He was taken up to the corpses of the slain soldiers, and one of the Hauhau chiefs asked him if he knew any of them.

Bent walked slowly past the dead, scrutinising each body carefully.

He recognised two of them. One was an old soldier who had been a comrade of his in the 57th Regiment, and who had afterwards joined the Colonial forces.

The other dead soldier he identified was von Tempsky.

The major's body lay there naked, with a deep tomahawk cut on the right temple, and the long, curly black hair matted with blood.

The other bodies were hacked about the head with tomahawks, this was the work of the Maori women, who delighted in mutilating the dead in revenge for those of their relatives who had fallen.

Before announcing his recognition of the white warrior's remains, he turned to the people and asked if any of them had taken from a pakeha officer a sword with an unusual curve in it, and a cap bound with a brass band.

A Hauhau jumped up and said, “Yes, I have them.”

“Show me which soldier you took them from,” said Bent.

The Maori, with von Tempsky's sword in his hand, pointed to the major's corpse.

“Well,” said Bent, “that is the body of Manu-rau, whom the pakehas called von Tempsky, and that is his sword.”

A great “Ah-h” came from the people, and the exultant possessor of Manu-rau's sword of wondrous mana went bounding down the marae, flashing the weapon above his head, turning his painted face from side to side in the hideous grimaces of the pukana, and thrusting out his tongue to an extraordinary length.

The Hauhaus were in a frenzy of excitement when they realised that the renowned Manu-rau was indeed lying dead before them.

Some of them proposed to drag the body out and cook it in the hangi, so that they might have the satisfaction of devouring their most dreaded enemy, and eating his heart, the heart of a tino-toa, a warrior indeed.

But Titokowaru, raising his sacred spear-staff, forbade the handling of the dead for the present.

Bent was now ordered to return to his hut, and the door was again fastened on him.

The proposal to cook and eat the bodies of von Tempsky and his comrades was debated in a wild korero.

Bent, from his eye-hole in the wall of the whare, saw Hauhau after Hauhau, the orators of the tribes, jump up, tomahawk or gun or sword in hand, and furiously declaim as they went leaping and trotting backwards and forward in the open space between the ranks of the victors and the dead, and the deeds of the battle-field were told again and again in great boasting words.

Von Tempsky's body, the pakeha-Maori had observed while on the marae, had not been mutilated, except for that tomahawk cut.

His heart had not been cut out, though Bent half expected it would have been.

The rite of the Whangai-hau, the ceremony of propitiation and burnt sacrifice following a battle, had not, however, been omitted.

On the previous night, Tihirua, the young war-priest, had cut open a soldier's body and had torn out the heart, which he had offered in smoke and fire as oblation to Uenuku, the God of War, chanting a karakia as he watched the heart of the hated white man smoking in the flames.

“Manu-rau's “famous sword, too, was set apart as a sacred gift to the gods, it was a parakia, or taumahatanga, a thank-offering for victory.

It became a tapu relic and was religiously preserved by the Hauhaus.

It is in their possession to this day.

Presently the bodies of the slain—the “Fish-of-Tu”—were ceremoniously apportioned amongst the several tribes represented in the village, as Bent again watched from his eye-hole in the wall.

One of the chiefs paced up and down past the pile of dead, with a stick in his hand. Pointing to a soldier's corpse, he cried,

“This is for Taranaki! Take it away”

Pointing to the others, he said,

“This is for Ngati-Ruanui—take it away This is for Nga-Rauru—take it away”, and so on until the whole of the dead men had been portioned out to the Hauhau clans to deal with as they deemed fit, subject always, however, to Titokowaru's approval.

The Nga-Rauru, the wild tribe of the Waitotara River, were the only men who actually took a body from the line of the dead.

Two warriors jumped up and, laying their weapons aside, seized a dead soldier by the ankles and dragged the corpse away.

One was Wairau, the other was the celebrated scout Katene Tu-Whakaruru.

This Katene was a strange fellow.

He had fought for some time on the Government side against his own countrymen, then he suddenly reverted to Hauhauism and barbarism, and led his warriors against his old friends and commanding officers, McDonnell and Gudgeon, with utter valour and ferocity.

Now he was to turn cannibal.

Katene and his companion dragged the body along the ground across the marae to the cooking ovens in the rear of the dwelling-huts, watched in silence by the people. “I could not say whose body it was,” says Bent, “but it was a man in good flesh”

When the two Hauhaus had hauled their body away to the hangi for a terrible feast, the tribes sat in silence for a few moments, gazing intently on their dead enemies lying there before them.

It was a calm, windless day, and the midday sun beat hotly down on that ghastly pile in the middle of the crowded marae.

Titokowaru rose, taiaha in hand. In his great croaking voice, he cried,

“E koro ma, e kui ma, tena ra koutou Tanumia te hunga tapu, e takoto nei, e tahu ki te ahi.

Kaore e pai kia takoto ki runga ki te kino. Te mea pai me tahu ki te ahi”

(“Oh, friends, men and women, I salute you, Bury the sacred bodies of the slain, lying before us here.

And burn them with fire, It is not well that they should be left to offend. They must be consumed in the fire”)

At this command, the people dispersed to collect fuel for a funeral pyre.

They brought logs and branches of dry tawa timber from the surrounding bush and from the firewood piles in the rear of the whares, and a huge pile of wood was built in the centre of the marae.

Even the little naked children came running up with their little hands full of sticks to cast upon the heap.

All the mutilated bodies of the white soldiers, except the one that had been dragged away, were lifted up and placed on the roughly levelled top of the pyre, which was about four feet high and about fifteen feet long.

Titokowaru ordered his men to place von Tempsky's body on the fire-pile first, and then lay the others on top of it.

The chief suspected, perhaps, that some of the Hauhaus wished to cook and eat Manu-rau's body, and he so far respected his gallant foeman even in death that he resolved to spare it that last degradation.

On top of the bodies, more wood was thrown.

Bent's hut door was now unfastened, and the natives called to him to come out.

What he saw he will tell in his own words,

“When I walked out on to the marae, I met two Nga-Rauru men I knew from Hukatere village, on the Patea River.

They had come to Te Ngutu-o-te-Manu with a gift of gunpowder to Titokowaru.

With them, I presently went down to the cooking-quarters to see what had become of the body that had been dragged away.

There we found a large earth-oven full of red-hot stones, and there they were engaged in roasting the white man's corpse.

They had prepared it for cooking in the usual way and were turning it over and over on the hot stones, scraping off the outer skin.

“The cannibal cooks looked around and asked me savagely what I wanted there.

They threatened that if I did not leave instantly they would throw me into the oven too, and roast me alive.

“I returned to the marae and was sitting amongst the crowd there sometime later, perhaps an hour, when I saw a man's hands and ribs, cooked, carried up.

The human flesh was placed in front of the two powder-carriers from Hukatere, who were sitting close to me.

The meat was in a flax basket, and a basket of cooked potatoes was set down with it.

This present of food was out of compliment to the visitors.

“The two Maoris refused to touch it, saying, ‘No, we will not eat man’

So the other natives ate it.

The rest of the body was also served round, and the people consumed the whole of it.

“Katene and Wairau were two of those who ate the cooked soldier.

I saw Katene squatting there, with a basket of this man-meat and some potatoes before him.

He took up a cooked hand, and before eating it sucked up the hinu, or fat, that was collected in the palm just as if he were drinking water.

The hands when cooked curled up with the fingers half-closed and the hollowed palm was filled with the melted hinu.

“Titokowaru did not eat human flesh himself.

His reason for abstaining was that if he ate it his mana tapu, his personal sacredness, would thereby be destroyed.”

The younger people in the pa were rather awestricken by the preparations for the cannibal feast and stood together, some distance away from the hangi.

“I stood with them,” says one Te Kahupukoro, who was a boy at the time, “I was afraid to join in the eating, but the savour of the flesh cooking in the ovens was delightful”

When the warriors, a little later on, were enjoying their meal of man-meat, some of the little children were heard calling out to their fathers: “Homai he poaka mou” (“Give me some pork to eat”).

They had seen the meat carried up in flax baskets and thought it was pork.

Now the white soldiers' funeral pyre was set alight.

An old man, Titokowaru's tohunga, or priest, walked up to it with a long stick of green timber in his hand, an unbarked sapling with a rough crook at one end.

He stood in front of the pile as the flames shot up and chanted a song.

Then, when the logs with their terrible burdens were well alight, he began a strange incantation.

Using his long stick with both hands he turned over the burning logs, pushed them closer together to create a fiercer heat, and forked the bodies into the midst of the blaze.

As he did so he recited a pagan karakia, the chant of the Iki, anciently repeated over the bodies of warriors when they were being cremated on the battle-field.

These were the words of the incantation (the mystic meaning underlying some of the expressions would require many notes to fully elucidate them)

Translation.

Ka waere, Clear them away,

Ka waere, Clear them away!

Ka waere i runga ma keretu, Sweep them into the earth,

Ka waere i raro ma keretu, Into the stiff and useless clay.

Kei kai kutu ma keretu, There let them perish and decay.

Kei kai riha ma keretu,

Whakatahia te kukakuka, Sweep man's flesh to earth again.

Whakarere te kukakuka,

Te roua atu, Fork them that way

Te kapea mai. Haul them this way

Roua ki Whiti, Fork them to Whiti,

Roua ki Tonga, Fork them to Tonga,

E tu te rou, To the ancient homes of man.

Rouroua Here I hold my fork erect,

Takataka te kape, I turn them this way, that way.

Kapekapea Quickly stir the funeral pile,

Ka eke i tua, Now this way haul, now that

Ka eke i waho,

Ka eke i te Maru-aitu Their spirits far have gone,

Te ihi nei, The flesh alone remains,

They have gone the way of Destiny.

Te mana nei, Their courage no longer stirs them,

Their pride and power have flown;

Nga toa nei. Their valour's gone

Ko tai ko ki, In the fullness of life they fell

Ko tai ko rea, Like the fullness of the tide!

Ko tai takoto ki raro. And now they lie naked before me

Ma peruperu They leapt in the war-dance,

Ma whiwhi They were strenuous in battle;

Ma rawea But they fell.

Haere ake ra te ihi o nga toa, Farewell! spirits of the brave

Te mana o nga toa, The pride and power of heroes!

Te whatu te ate-a-Nuku Heart of Earth, and heart of Heaven,

Te whatu te ate-a-Rangi. For both joined to produce you

Huri ana te po, Now turns the night,

Huri ana te ao, It turns to day again.

He rangi ka mahea, The clouds obscure the sky,

He whai ao, We search for light,

He ao marama The perfect light of day!

The people sat there on the marae, silently watching the burning of the dead.

Far above the trees of the surrounding forest rose the thick black column of smoke from the blazing pile.

It went up as straight as an arrow, unswayed by any breath of air, to a great height.

To the savage watchers, it was verily the incense of the battle-field, rising to the war god's nostrils.

“Now and then,” says Bent, “a body would burst, and the blaze of flame and the smoke would leap straight up, high into the air.”

Long the Hauhaus gazed at the dreadful crematory blaze on the palisaded marae, replenishing the fire with dry logs as it burned down until all the dead were consumed, and nothing but a great heap of charcoal and ashes remained.

The first of the below posts has a list of the previous posts of Maori Myths and Legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-war-was-declared-between-tainui-and-arawa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-hatupatu-and-his-brothers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hatupatu-and-his-brothers-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-the-emigration-of-turi-an-ancestor-of-wanganui

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-continuing-legend-of-turi

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turi-seeks-patea

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-manaia-and-why-he-emigrated-to-new-zealand

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-love-story-of-hine-moa-the-maiden-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-te-kahureremoa-found-her-husband

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-magical-wooden-head

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-art-of-netting-learned-from-the-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-kanawa-s-adventure-with-a-troop-of-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-loves-of-takarangi-and-rau-mahora

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/puhihuia-s-elopement-with-te-ponga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-te-huhuti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-trilogy-of-wahine-toa-woman-heroes

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-modern-maori-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hine-whaitiri

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/whaitere-the-enchanted-stingray

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turehu-the-fairy-people

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawariki-and-the-shark-man

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/awarua-the-taniwha-of-porirua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hami-s-lot-a-modern-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-unseen-a-modern-haunting

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-death-leap-of-tikawe-a-story-of-the-lakes-country

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/paepipi-s-stranger

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-of-maori-gratitude

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/some-of-the-caves-in-the-centre-of-the-north-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-man-eating-dog-of-the-ngamoko-mountain

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-from-mokau-in-the-early-1800s

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/new-zealand-s-atlantis

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-dwellers-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawa-mountain-and-tarao-the-tunneller

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-fragrant-leaf-s-rock

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-waikato-river

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/uneuku-s-judgment

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/at-the-rising-of-kopu-venus

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/harehare-s-story-from-the-rangitaiki

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/another-way-of-passing-power-to-the-successor

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-of-wairaka

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-how-mount-tauhara-got-to-where-it-is-now

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ana-o-tuno-hopu-s-cave

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/stories-of-an-enchanted-valley-near-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/utu-a-maori-s-revenge

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/where-tangihia-sailed-away-to

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-fall-of-the-virgin-s-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-first-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-maori-detective-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-second-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-a-maori-heroine

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-kawhia

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-stealing-of-an-atua-god

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/maungaroa-and-some-of-its-legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-mokia-tarapunga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-memory-of-maketu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-taupo-region

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-the-taniwha-slayers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-witch-trees-of-the-kaingaroa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/there-were-giants-in-that-land

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-rotoiti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-lagoons-of-the-tuna-eels

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-takitimu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-white-chief-of-the-oouai-tribe

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/tane-mahuta-the-soul-of-the-forest

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-maori-magic

with thanks to son-of-satire for the banner