Let me tell you something about death

Let Me Tell You Something About Death

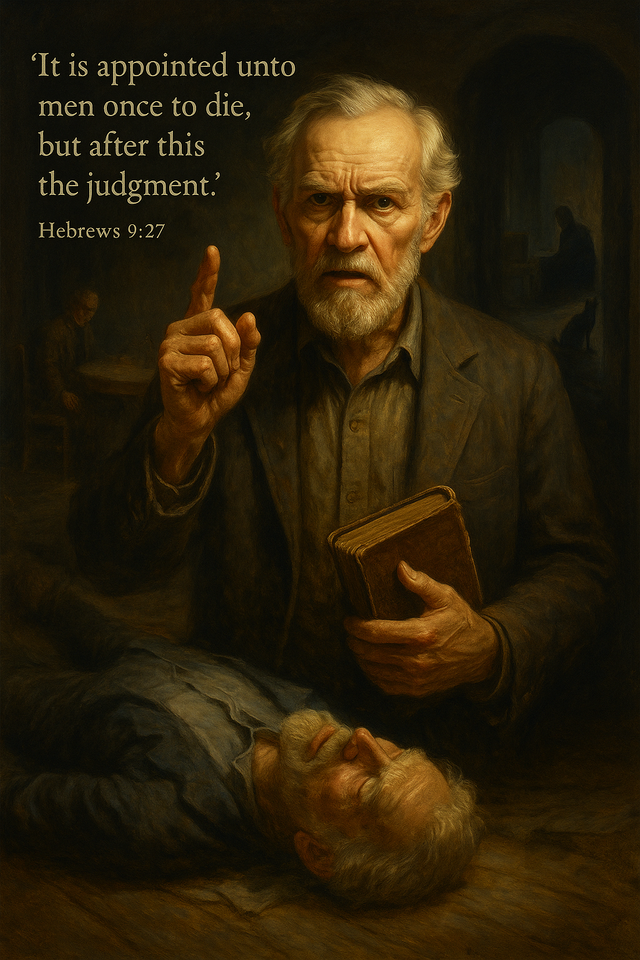

“It is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment.”

— Hebrews 9:27 (KJV)

Let me tell you something about death—it’s not what the movies told you. It doesn’t always wait for last words or give you one final breath to whisper a prayer. Sometimes it doesn’t even knock. It just walks in.

People think they have time. Time to get right. Time to clean up. Time to call Mama. Time to make peace. But they don’t. I’ve seen it with my own eyes—death shows up when the calendar’s blank, when the rain is soft, when the world is still turning like nothing’s wrong.

I’ve found people with lottery tickets still clenched in their hands. I’ve held men while their blood soaked into the sidewalk. I’ve sat with strangers as they took their last breath, with Masons lining up behind me too late. I’ve seen the dog barking over its dead master, and the hoarder who never made it out of the maze he built for himself.

Most of them didn’t think it would end like that. Some thought they had years. Some thought they had hours. All they really had was now.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about truth. Because once you’ve seen what I’ve seen, you stop playing games. You stop assuming people know the gospel. You stop pretending death is polite.

What you’ll read in these pages are real stories. I didn’t write them to be poetic. I wrote them because I couldn’t forget them.

Some of these people may have called on Jesus. Some may not have. But they all had one thing in common:

They ran out of time.

And every time I stood over one of them, the same thought echoed in my heart:

I should have said more.

Let me tell you something about death. It doesn’t always come with thunder. Sometimes it shows up on a blistering summer day, quietly sitting down in a folding chair just to pull the trigger without flinching. That’s how it came for Bob. It was an extremely hot day and I was working on the engine of my truck. It was an old 1969 box truck—a Grumman. I bought it for $1,300, I think. I kept all my lawn equipment in there, drove around, did what I needed to do. But I was always having to work on it. My son was always trying to help. My oldest daughter too—she was always getting tools and asking if I needed something to drink. This particular day, I think my Son was around nine, and that would make my Daughter eight. Irish twins. It was summertime, and there was something wrong with the engine—maybe just the radiator—but I had the hood up and we were working on it. The house we lived in had a decent-sized piece of property, and there was a dirt road that ran the full length of the back. It dead-ended into the woods. Across that dirt road, on a triangle-shaped piece of land near the railroad tracks and a small train bridge, there were initially four or five mobile homes. Eventually, there were only three. In one lived a man who had married a Vietnamese or Singaporean woman while overseas. He raised bees in the back and she would sweep her front yard—which was all dirt—with a palm-leaf broom she’d made herself. She swept it every day. The next trailer, behind that one, housed a man who claimed to be the head of the Ku Klux Klan in the area. One day, he walked up to me over the back gate, introduced himself, and handed me a card. It didn’t have his real name—just “Dragon” and “Invisible Empire.” I found it ironic that an invisible empire needed business cards. I’d met some real hard men in the South, and I didn’t see anything visionary or worthy of surpremist delusions about this guy. But he mostly minded himself, got drunk a lot, listened to loud Southern rock, and stayed in his corner. Then there was the trailer directly behind ours , it was home to a black family whose kids we took to church quite often. Their mother was impeccably clean, obviously loved her children, but seemed to go through boyfriends like tissue. Things would get wild sometimes—like something straight out of Jerry Springer. I remember one day she had an argument with her boyfriend, who drove a red Camaro. She was twice his size and so angry, she tried to drag him out of the car. He tried to drive off or drive over her but she jumped in front of the car with a cinderblock and smashed the windshield while screaming at the top of her lungs. It was like a parody of a stereotype—but it was real. Of course, with the Klan guy living behind them, there was not much friendly interaction between those households… unless the boyfriend—who fancied himself a pseudo–Black Panther—and the Klan guy both got drunk and hung out together. Which happened. Strange, but it happened. That mom had three boys, I think, and maybe a girl, i think there were a couple different dads but they looked alike. You could tell they were brothers. They were friends with my kids. We took them to church regularly until one day, the mother told them they couldn’t go anymore. I went to talk to her about it, and shared the gospel with her. She said something like, “You don’t have to go to church to go to heaven—God understands.” I told her it’s not about being good or bad. What matters is Jesus, because all have sinned and come short of the glory of God. Some people have done a lot of sin, and others a little—but without Christ, they’re in the same place. And she said, “Well, I don’t think that.” I said, “Even Hitler liked dogs and loved his family—that doesn’t make him a good person.” She said, “Maybe it doesn’t mean he was a bad person either.” I said, “Ma’am, he was responsible for the deaths of millions.” And she replied, “Well, maybe they had it coming.” I stood there stunned. “World War II, ma’am—millions of Jews.” And she said, “Look, I went to school 20 years ago—you don’t expect me to remember all that.” That’s when I realized I’d have to start my argument way further back than I thought. Anyway, one of her boys came crying to me. His mom wouldn’t let him go to church anymore. When I asked why, he said she’d accused him of “acting white.” He looked at me and said, “If going across the street to those white folks makes me white, I’d rather be white than black like this. They feed us, they don’t curse at us, and they treat us like we matter.” There was more going on in that house than I knew. Then there was Bob. He and his wife had been there the longest. I think he owned his trailer. The rest probably rented. Bob was a Freemason. Nice guy, but hard to talk to about the Lord. He had a little garden, but there was too much shade for much to grow. His wife had threatened suicide more than once. Bob always seemed tired, like a man holding on to the last rope of peace he had left. I was working on the truck that day—hood up, elbows deep—when I heard yelling from Bob’s trailer. Just sounded like a typical fight. But then it got louder. Sharper. I stayed focused on the truck. My son was inside the cab. Then I heard Bob yelling outside. He couldn’t get in—she had locked him out. Then he yelled something like, “If you’re going to kill yourself, then I’m not staying in this trailer alone with all these crazy neighbors!” I looked up. He was dragging a folding lawn chair—green and white plastic slats, aluminum frame. The kind you take to the beach. He set it up in the yard by the road, sat down in it, buttoned up his blue checkered shirt, shouted one last thing toward the trailer… Then he put the barrel of the revolver into his mouth and shot himself. The sound of the .38 going off was unmistakable. It wasn’t loud. It was dull and final. Like a period at the end of a sentence God never wrote. I jumped down and ran. My son followed me. I turned and said, “Go back to the house. Tell your mother to call the police.” I don’t remember all the details, but Bob didn’t fall out of the chair. He kind of slumped and slid. I think I pulled him down gently. I remember sitting cross-legged on the ground with his head in my lap. He was breathing, but his color was changing. No exit wound. No blood out of his mouth. Maybe the bullet hit his dentures and lodged. And I just started singing. And praying. “Bob, if you can hear me, you don’t have much time. Jesus died for you. He rose again. And this doesn’t have to be the end. But if you don’t know Him, you only have maybe a minute or two. Call out to Him now. Please, Bob…” His breathing slowed… and then stopped. The paramedics arrived, but I was still holding his head. I told them, “You start CPR and blood’s gonna go everywhere.” They did anyway. As soon as they compressed his chest, blood poured out. Like squeezing a red tube of toothpaste. Soon after, his wife was brought out of the house on a stretcher. She’d taken pills—this time she wasn’t kidding. She was dead too. All I could think was: If Bob died and went to hell, he would not be alone. The Klansman. The woman in chaos. The drunk boyfriends. The proud. The silent. The decent ones who never repented. All standing together before the throne, speechless. Let me tell you something about death: And I’ll still be here thinking… I should have said more. Let me tell you something about death: It doesn’t always come with warning signs. There doesn’t have to be a cataclysm. There doesn’t have to be an asteroid or the sound of war. It can be a peaceful, beautiful, rainy day—and then, out of nowhere, you’re gone. This man lived in a duplex along Front Street, in or near the town where we lived. I used to go door to door or just make general visits, wherever I felt led. I didn’t always have a plan. Sometimes I stood outside a supermarket handing out tracts. Sometimes I just walked or rode to the park, or down a street, Bible strapped to the back of my bicycle—sometimes even a thesaurus, dictionary, or concordance in the basket in case I needed to study or answer a question. That day I was riding down Front Street, railroad tracks on my right, the duplexes on my left. These were the same tracks that ran past where Bob died—maybe a mile down. As I rode by, I happened to glance through a large open-pane window and saw an elderly man sitting very upright at a small round table. His back was straight, shoulders square. The door was just to his left. I remember thinking, That old man lives alone. I’m going to stop on the way back and talk to him about the Lord. So I kept going. I don’t remember where I was headed—maybe the market, maybe just making visits, or reading Scripture somewhere. But I know I was gone at least an hour or two. When I came back, I approached the same duplex from the other direction. This time the railroad tracks were on my left and his house on my right. I pulled up to the curb and walked along the sidewalk toward the door. But before I could knock, I looked through the same window and saw… He was still sitting there. Same table. Same position. Only this time, I could see more clearly. His left hand was clenched around what looked like lottery tickets. His eyes were wide open. He had a strange, stiff expression on his face. I thought maybe he was in some sort of daze. I tapped the glass. He didn’t flinch. I knocked again—nothing. That’s when I noticed something small—a fly had landed on his cheek. And then I had this awful thought: If that fly crawls across his eye and he doesn’t blink, he’s dead. Sure enough, it did. And he didn’t move. He was dead. Still sitting up. Upright. Clutching lottery tickets like maybe he had won something—or maybe he was just holding onto a last hope. I ran to the house next door and asked to use their phone. Told them what I saw. They were startled but kind. I called the police. When they arrived, I explained I hadn’t been inside—I just happened to see him earlier that day and felt led to return and talk to him. But I didn’t stop when I first saw him. I waited. I told them, “I was going to share Jesus with him.” One of the officers looked at me sideways. “How did you know he was dead?” I said, “He’s got a fly crawling across his eyeball. If he’s not dead, he’s the best statue I’ve ever seen.” They took my information. Asked a few more questions. Then they went inside and confirmed it: the man had died, still sitting upright at the table. I never knew his name. I never found out how long he’d been there—if he died just after I passed the first time, or if it had been longer. I just know this: I meant to stop. I meant to say something. I didn’t. I delayed. I thought I had time. Let me tell you something about death: Sometimes you don’t get the chance to say what you need to say. And sometimes the only thing worse than being too late… is knowing you were almost right on time. I don’t know if he ever heard the gospel before. I don’t know if anyone ever told him that Jesus died for him. But I know that day—it wasn’t me. He died with lottery tickets in his hand. Maybe he won. Maybe he didn’t. Maybe he thought he had more time to make peace with God. Maybe he was already gone when I first passed. But I didn’t knock. I didn’t stop. And the thought that haunts me still is: I should have said more. Let me tell you something about death: Sometimes you do get a chance—one final moment to speak the truth before the shadows fall. And when that window opens, you'd better be bold enough to step through it. Because if you don’t, someone else might—and they might not be bringing life with them. It was 1999, and my grandmother—my Nana—was dying. She had been in and out of the hospital for a while, dealing with dialysis and other serious issues. She was born in 1912. I’d been doing everything I could to help—bringing her vitamin-rich popsicles packed with antioxidants, encouraging her to eat, praying over her. I don’t want to go too deep into what was going on with her right now, but during those weeks, I was in and out of that hospital constantly. Intensive care. Waiting rooms. Long walks down sterile halls. Always hoping today wasn’t the day she let go. One afternoon I was in the elevator, quietly singing Amazing Grace. Not for show—just for the Lord. A woman was riding with me, a black woman, very sweet. She told me she went to the big Baptist church in Lakewood, the one that’s since been bought out by the Orthodox community. She heard me singing and we struck up a conversation. She told me about her father-in-law—an older white man—who was in critical condition. He wasn’t saved, and she was worried. So I asked her: “Would you mind if I came to pray for him, maybe talk with him a bit?” She agreed. We went down into the ICU. Her father-in-law was stretched out on his back—tall, solid, probably once very strong. You could tell this man had been rugged, maybe a coal miner or a laborer of some kind. His body had lost its fight, but the outline of strength was still there. Big hands. Heavy frame. Now nearly lifeless. His breathing was ragged—every inhale like a man hanging onto his last bit of earth, afraid to let go. His son—her husband—was there, along with another family member. They were all white. She was black. I asked the son if I could talk to his father, and he said yes, “Go right ahead.” I introduced myself to the old man, grabbed his hand, and asked if he could hear me. He squeezed. It was tight—intentional. He was weak, but present. I leaned in close. The smell in the room was unforgettable: medicinal, sterile, but with an edge I recognized—a jaundiced, almost metallic smell. I had smelled it before, years earlier, when my grandfather’s sister Dorthe was dying. It’s the smell of a body winding down. I got closer and spoke softly. “Sir, I’ve been talking to your daughter-in-law. She’s worried about you, and she asked me to come pray. I don’t know your condition, but I want to share something important.” He squeezed my hand again. So I shared the gospel. I told him Jesus came for sinners, died in our place, rose again from the dead. I told him about grace—that Christ could forgive all his sins, no matter how many, and give him a righteousness not his own. I told him it wasn’t about being good enough—it was about Jesus being perfect in our place. “Do you believe that?” I asked. He squeezed again. “Would you like to receive Christ right now? You can do it. Right here. Just call on Him. Ask Him to forgive you. Ask Him to save you.” He squeezed again. Tighter. Then, a tear. A single tear ran down his cheek. He couldn’t speak, but his eyes moved. His grip tightened. His breathing grew slower. I told him about the thief on the cross—that he didn’t have time to clean up his life, but he had just enough time to say, “Lord, remember me.” And Jesus said, “Today thou shalt be with me in paradise.” I said, “Sir, you can be with Him too. But it has to be now. You don’t have much time.” And then I began to sing. I sang: “And somehow Jesus came and brought Then I sang Amazing Grace. And as I sang, more people came in—his brothers, friends, people from his life. That’s when I saw it: Masonic regalia. Little white aprons. Square and compass jewelry. Men whispering in ceremonial tones. They were there for their ritual. But thank God—thank God—I got to him first. Because if they had gotten to him before I did, they would’ve distracted him, misled him, wrapped him in symbols and secrecy instead of truth and salvation. The enemy would’ve surrounded him in false light when what he needed was the true Light. The next day, I ran into the family again. They told me he had passed away. They cried. I cried. Then the daughter-in-law asked if I’d say a few words at the funeral—and maybe sing Amazing Grace. I said I’d be honored. The funeral was held in a large church—her church. Nearly everyone there was black, gathered to honor a white man in a coffin. It was beautiful. I stood and said what had to be said: “It’s never too late to call on the name of the Lord… but it can be too late if you wait too long.” And I sang. Let me tell you something about death: I believe he called on Jesus that day. And I believe the Masons were too late.Chapter One: Bob

It comes for everyone. And when it does, you won’t care what your title was, what color you were, or who lived in the trailer next to yours. You’ll care whether you knew the One who conquered it.Chapter Two: The Man on Front Street

Chapter Three: Before the Masons Came

“I heard an old, old story,

How a Savior came from glory,

How He gave His life on Calvary,

To save a wretch like me…”

To me the victory…”

There may be just one moment left—the last window before eternity. And when it comes, you’d better already know the One who holds the door.Chapter Four: The CVS Bench

Let me tell you something about death: It can come when everything seems normal. There doesn’t have to be a car crash, or a diagnosis, or a war. It can happen on a peaceful, rainy day—while you're reading the paper—without warning, without time to think. One minute you're here. The next, you’re gone.

This happened at a CVS pharmacy. I was just trying to get a few dollars out of the ATM before heading to the flea market. Nothing spiritual, nothing dramatic. It was just part of a normal day.

As I pulled in, I noticed a group of people standing around near the front of the building, between the sidewalk and the parking lot. They weren’t rushing or shouting—just hovering, uncertain. Curious. That kind of frozen hesitation you see when people are watching tragedy unfold but don’t know what to do yet.

As I looped around toward the ATM, I noticed something else—something red trailing along the sidewalk, like a line drawn from the edge of the crowd. Then I saw a man lying on the ground. He was twisted onto his side, barely visible. I parked, jumped out, and walked over to the scene. No police. No paramedics. Just bystanders. One woman in a pharmacy smock, and several others looking stunned.

As I got closer, it became clear: this man had been pinned against the wall. It looked like something invisible had crushed him into the side of the building and then vanished. The bench he’d been sitting on—one of those metal-framed types bolted into the sidewalk—had snapped from its bolts. The supports had buckled and bent backward like broken fingers. And now the man lay twisted in the remnants of it, half-conscious, blood everywhere.

What happened was this: an elderly woman, possibly with Alzheimer’s or some other cognitive issue, had tried to park in the handicap space. But instead of braking, she hit the gas, jumped the curb, and slammed her car into the man while he sat peacefully on the bench waiting for his wife. The force pinned him to the wall. Then, realizing she wasn’t in the correct space, she backed up, pulled into the actual handicap spot… and went inside the store. She had no idea what she’d done.

By the time I got to him, the man was still alive—but barely. He had a glazed look in his eyes. His face was against the cold, wet pavement, and I couldn’t bear to leave him like that. So I knelt down, got underneath, and gently lifted his head off the concrete. I held it in my hands. I cradled him. And I prayed.

“Sir, I don’t know if you can hear me. But if you can, please listen. You don’t have much time. If you’ve never asked Jesus Christ to save you, do it now. Right now. Deep in your heart, believe that He died and rose again. Confess Him. Trust Him. You don’t have to have all the words—just faith. Don’t wait. Don’t let go.”

I could see he was still breathing, but it was shallow. There was so much blood. The bench had punctured his leg—probably his femoral artery. I saw muscle, tissue… not just a cut, but a wound that meant this man wasn’t going to last long. He was almost unconscious already.

That’s when the police showed up. One officer approached and said, “We need to begin compressions. We have to keep his heart going.” I told him, “You can try, but look—he’s bleeding out. If you press on him, it’s going to force all the blood out of him. It’ll be like squeezing toothpaste.”

But they had their procedure. They did it anyway. As they started compressions, the blood shot out. A terrible, pulsing stream—like something you'd see in war. They were trying to keep him alive, but it was already too late. His body was emptying faster than they could stop it.

I told them they needed to apply a tourniquet. They were working fast, but I knew in my gut—it was over.

They finally got him onto a stretcher, loaded him into the ambulance. I stood back, blood on my hands, his blood. His head had never touched the pavement. I made sure of that.

Then I went inside. I wanted to find the woman. And there she was—walking through the store aisles like nothing had happened. She was holding a bottle of shampoo or something, just browsing. Oblivious.

Let me tell you something about death: It doesn’t care if you’re in a bad neighborhood. It doesn’t care if you’re on your way to church or going to pick up prescriptions. It doesn’t wait for drama or catastrophe. Sometimes it just steps off the curb and lands on your head.

Later on, I was contacted to give a statement. I had to testify, maybe not in a courtroom, but in a legal setting—some kind of deposition. CVS had to answer for it. Evidently, they had installed those benches even though they were warned about the risk. For years afterward, they didn’t replace them. They didn’t install protective posts or barriers.

But you’ll notice now—look at almost every gas station, every store, every pharmacy—you’ll see those thick concrete pillars outside. Those weren’t always there. They were added because too many people got run over. Maybe, just maybe, what I witnessed helped change that.

But those pillars can’t stop death.

I think sometimes about Adam and Eve. God said, “The day ye eat thereof, ye shall surely die.” But they didn’t drop dead immediately. Not because God lied—but because God showed mercy. He made a covering. A sacrifice. But I wonder if, over time, they forgot what death really meant. Maybe it took years. Maybe they’d gotten used to growing old. But then one day, their own son murdered his brother—and suddenly, they understood.

Death doesn’t always happen to you. Sometimes it happens through you. Sometimes your sin doesn’t kill you—it kills someone you love.

Let me tell you something about death:

It comes fast. It comes without apology. And it doesn’t ask if you’ve made peace with God first.

I don’t know if that man had ever heard the gospel before that day. I don’t know if he heard me whisper it to him. I don’t know if, in those final seconds, he believed. But I know he heard it. He had a witness. He had a chance—even if only for a heartbeat.

And I know this too:

I should have said more.

Epilogue: And They All Have One Thing in Common

Let me tell you something about death:

It doesn’t care who you are.

It doesn’t care how long you’ve lived, or what you’ve built, or how neatly you folded your laundry, or whether the neighbors thought you were decent.

It comes.

And when it does, it always leaves something behind—regret, questions, silence… or the scent of eternity.

I’ve told you four stories in these pages.

But there are others.

There was the old man I found stretched across his hallway—pants around his ankles, eyes frozen wide in terror, as if the moment of death had caught him by surprise. His little dog barked and yelped beside him, as if trying to call out, “Somebody help. He’s not getting up.”

There was another man—a hoarder—who rolled over in his bed and never got back up. I found him face down in a sea of newspapers stacked two feet high, the house had the smell of decay and CATS. His mobile home was packed so tightly with trash that you could only move through six-inch-wide trails from one room to another. No space for dignity. No space for life. No space for death, really. Just silence, and dust, and the weight of what never got thrown away.

There’ve been others.

There will be more.

And though their circumstances were all different—some loud, some quiet, some violent, some barely a whisper—they all had one thing in common:

They ran out of time.

Some were warned.

Some never saw it coming.

Some had someone there to pray.

Others died staring at the ceiling. Alone. Unfinished. Unready.

And in every case, the same thought runs through me like a cold wind:

I should have said more.

Maybe I said enough. Maybe I didn’t.

But the weight never leaves.

Because you only get so many chances to say the thing that matters.

And death doesn’t reschedule.

Let me leave you with this:

There is no amount of morality, no measure of decency, no pile of good deeds that will prepare you for that moment.

The only thing that matters—the only thing—is whether you knew Jesus Christ. Whether He knew you.

- Not whether you went to church.

- Not whether your parents were religious.

- Not whether you “believed in God.”

No, friend. Whether you repented and believed the gospel.

And if you haven’t done that yet, I plead with you now…

- Don’t wait for the folding chair.

- Don’t wait for the window.

- Don’t wait for the bench or the hospital or the hallway.

Say yes while there’s breath in your lungs.

Because the gospel isn’t just for dying people—it’s for the living who know they soon will.