Dinn Righ Rediscovered

Dind Ríg, also known in English as Dinn Righ and in Modern Irish as Dionn Rí, is an ancient Irish stronghold on the River Barrow in County Carlow. It is believed to have been a royal citadel sometime during the Iron Age and is featured in a number of traditional tales. Its location is uncertain and still the subject of scholarly debate. Since the 19th century it has been commonly identified with Ballyknockan Moat near Leighlinbridge, though this has had its critics.

Name

The earliest form of the name is the Old and Middle Irish Dind Ríg. The first word comes from the Proto-Celtic *dindu, meaning peak, tip. Among its definitions in the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of the Irish Language the following may be noted:

(a) height, hill ... (b) fortified hill, walled or fortified town, citadel, stronghold ... (c) stead, notable place ... (d) mansion, court ... (e) pinnacle, peak ―Quin 215

In Modern Irish, dind has become dionn, which Patrick S Dinneen defined thus in his Irish-English Dictionary:

Dionn, g. dinn, pl. -a, m., a fortress ; a royal palace ... fortified hill ; a hillock ... ―Dinneen 341

The second word, Ríg is the genitive plural of the Old Irish rí, “king”. The literal translation of Dind Ríg is Fortress of Kings (O’Rahilly 13)

Location

Dind Ríg is mentioned twice in the Annals of the Four Masters, under the years a.m. 3267 and a.m. 4658. Anno Mundi [Year of the World] 3267 corresponds to 2733 bc. Under the previous year it is recorded that: the Firbolgs took possession of Ireland at the end of this year. Slainghe, Gann, Genann, Seangann, and Rudhraighe, were their five chieftains. These were the five sons of Deala, son of Loich.

The Age of the World, 3267. Slainghe, son of Deala, was king of Ireland for a period of one year ; and he died at the end of the year, at Dinn-Righ, on the brink of the Bearbha. ―O’Donovan 15

To this the editor & translator John O’Donovan added the following note:

Dinn-Righ : i. e. the Hill of the Kings, otherwise called Dumha-Slainge, i. e. Slainge Mound. This was a very ancient seat of the kings of Leinster. Keating describes its situation as on the brink of the River Bearbha [the Barrow], between Carlow and Leighlin. This place is still well known. It is situated in the townland of Ballyknockan, about a quarter of a mile to the south of Leighlin-Bridge, near the west bank of the River Barrow. Nothing remains of the palace but a moat, measuring two hundred and thirty-seven yards in circumference at the base, sixty-nine feet in height from the level of the River Barrow, and one hundred and thirty-five feet in diameter at top. ―O’Donovan 14–15 fn

Roderick O’Flaherty also associated Dind Ríg with Sláine mac Dela in his Ogygia:

Slangy, at the expiration of one year, was interred at Dumhaslainge in Leinster. [Footnote: Now Denrigia [Dinrigiem in the original Latin accusative], on the banks of the river Barrow, between Carlow and Lethglinn.] ―O’Flaherty & Hely 2:16

Returning to the Annals of the Four Masters, a.m. 4658 is equivalent to 1342 bc:

The Age of the World, 4658. Cobhthach Gael Breagh, son of Ugaine, after having been fifty years in the sovereignty of Ireland, fell by Labhraidh Loingseach, [i. e.] Maen, son of Oilioll Aine, with thirty kings about him, at Dinn-righe, on the brink of the Bearbha [Barrow]. ―O’Donovan 77

In a footnote to this, O’Donovan adds:

In a fragment of the Annals of Tighernach, preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Rawlinson, 502, fol. 1, b. col. 1, this fact is also mentioned, and the place is called Dinn-Righ in Magh-Ailbhe, and the house or palace Bruidhin Tuama-Teanbath. The Annals of Clonmacnoise also mention this burning of “Cobhthach, together with thirty Irish princes, on the Barrowe side, at a place called Dinrye.” ―O’Donovan 76

O’Flaherty also recounted the destruction of Dind Ríg:

Laurad, after the murder of his father and grandfather, being banished into Gaul, in a few years after brought a great number of strangers in a large fleet ... into the harbour of Wexford. Afterwards he rushed into the palace of Cobthach at Dinrigia, near the river Barrow, and put the king with thirty of the nobility to the sword, and laid the entire palace in ashes. ―O’Flaherty & Hely 2:137

Another 17th-century historian, Geoffrey Keating, also recorded the location of Dind Ríg. He identified it as the fortified residence of Sláine mac Dela, the same Slainghe mentioned in the Annals of the Four Masters:

... it is from him is named Dumha Slainghe, otherwise called Dionnriogh, on the bank of the Barrow, between Carlow and Leighlin, on the west side of the Barrow, and that it was his fortified residence, and that it was there he died. ―Keating et al 1:30–31

The translator David Comyn notes that Leighlin refers to Leithghlinn, a village now known as Old Leighlin to distinguish it from the younger Leighlinbridge, which lies about 3.5 km to the east.

Ballyknockan moat

In 1839 Thomas O’Conor of the Ordnance Survey of Ireland identified a structure near Leighlinbridge known locally as Ballyknockan Moat as Dind Ríg, an identification that is still routinely repeated to this day. Here moat is the same word as mote or motte, meaning a hill, especially one on which a fortress has been built (Oxford English Dictionary). The following is taken from O’Conor’s letter of 30 June 1839 to Thomas Aiskew Larcom, the officer in charge of the Ordnance Survey’s day-to-day operations:

But first I have to give notice of Bally-Knockan alias Maudlin Moat in the Parish of Wells.

This moat is a very large and conspicuous object, situated about ¼ mile from Leighlin Bridge to the south and overlooking the River Barrow, to the west of which it is placed. It stands on a high ridge which here abruptly rises over a flat lying between it and the river. The distance from the base of the foss[e] that surrounds the moat to the river across the flat ground is about 138 yards. The diameter of the mound at top, which is tolerably level, is from South to North 47 yards = 141 feet and from East to West 46 yards = 138 feet. The circumference at the top extremity was 151 yards ... ―O’Conor 30 June 1839 (pages 249 ff)

After describing in considerable detail the dimensions and situation of the earthwork, O’Conor proceeds to give his opinion as to its identity:

Though the ancient name of this moat is not remembered, there is still every certainty that it is Dinn Righ, Munitio regum [Latin: “Fortress of Kings”], which was the palace of the Leinster Kings. In Note (1) to the Ogygia below referred to, O’Flaherty states that Dumhaslainge was now (i.e. in his time [=1685]) Denrigia, on the Banks of the Barrow between Carlow and Leighlin. Keating is still more definite (see his preface to 42, referred to infra) when he states that Dionn Righ was situated on the bank of the Barrow between Carlow and Old Leithghlinn (and) to the west side of the Barrow.

The situation of the feature described in this letter, though it is not on a direct line between Carlow and Old Leighlin, agrees in every other respect with that of Dinn Righ as given by O’Flaherty and Keating already cited. It is to be noted here that the river formerly ran at C[arlow] as shown on the section from West to East [...] that accompanies [this letter]. The high ground which the moat occupies was then the bank of the river. Indeed, it may be properly so called still. See now the words above on this.

Its very character as to size and form testifies much to the truth of the identity. ―O’Conor 30 June 1839 (pages 249 ff)

Despite his confidence, O’Conor’s opinion has not gone unchallenged. The first scholar to question it was the Irish historian Goddard Henry Orpen, in his paper Motes and Norman Castles in Ireland, which was published in The English Historical Review in 1907:

Inferentially indeed an attempt has been made to identify certain existing fortified motes with certain ‛duns’ or ‛lisses’ or ‛raths’ mentioned in pre-Norman documents. But in the first place it is important to observe that the supposed Celtic fortress is in each case ascribed to some very early―often, indeed, to some prehistoric―period. Thus ... Burgage or Ballyknockan Mote, near Leighlin Bridge, is equated with the Dinn Righ, a fort of some entirely prehistoric kings of Leinster, said to have been abandoned even in prehistoric times ... ―Orpen 231

Orpen identifies Ballyknockan Moat with an Anglo-Norman castle attributed by Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) to Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath:

- Castrum Lechliniae, super nobilem Beruae fluvium ([upon] the [noble river] Barrow) a latere Ossiriae (i.e. on the west bank) trans Odronam in loco natura munito [towards Idrone, in a naturally fortified place―Giraldus Cambrensis 5:352].―The castle was not, therefore, close to Old Leighlin, which is more than two miles away from the river; nor was it, as is usually supposed, the Black Castle at Leighlinbridge, for that is on the east bank and not in a place naturally strong. The position exactly suits the fort called Ballyknockan, or Burgage Mote, in the parish of Old Leighlin, about a quarter of a mile south of Leighlinbridge. This mote is situated on a sort of promontory on the west side of the river-cutting, with very steep slopes towards the Barrow on the east and towards a stream [the Madlin] on the south, and was formed by doing little more than digging a deep trench round it and throwing up a rampart, especially on the west side. I must add that I was in error in doubting that it was a real mote. I have since visited it, and find that it is always called Burgage or Ballyknockan Mote. The name of the adjoining place is Burgage House, a significant name, indicating that there was once a burg or English borough there, such as generally grew up in the immediate neighbourhood of the more important early castles, and often vanished with them. The top of the mote is raised some ten feet above the level of the land on the west, and is sixty-nine feet above the Barrow. I thought too that I could trace a large square bailey to the west. There is a shallow fosse on the top of the cutting made by the stream to the south; the road to the west is in a cutting, and may occupy the fosse here, while there is a rather large field fence on the remaining side, though here the fosse, if it ever existed, has been filled up. O’Donovan’s identification of this mote with the Dinn Righ of legendary fame is not satisfactory. It was based on a statement of Keating’s that ‛Dumha Slainghe, otherwise called Dionnriogh, was on the bank of the Barrow between Carlow and Leighlin, on the west side of the Barrow.’ Ballyknockan Mote, however, is not between Carlow and Leighlin, but is south of Leighlin Bridge. Again, Tighernach says that Dinn Righ was in Magh Ailbhe, but O’Donovan elsewhere places this plain in the south of Kildare. [Footnote: O’Donovan makes Magh Ailbhe include the northern part of the barony of Idrone, but I suspect that he had no grounds for this southern extension except the supposed site of Dinn Righ.] However even if Ballyknockan Mote was the fortress which Keating had in view, Slainghe is said to have died 1,900 years b.c., and Dinn Righ is said to have been abandoned in entirely prehistoric times, and I think few people will now believe that the earthworks at Ballyknockan can possibly be so old or that Keating’s identification was more than an uncritical guess. ―Orpen 245–246

In September 2024 I too visited the site to see for myself. Ballyknockan Mote has the classic profile of an Anglo-Norman motte-and-bailey: it comprises a steep-sided, flat-topped central mound, somewhat resembling an upturned bucket, surrounded by a narrow but deep defensive trench or fosse. Both sides of this fosse are quite steep. This is very different from the typical profile of the ancient Irish rath. The Irish were farmers. Their wealth lay in their cattle. In time of war, they needed a place in which their valuable cattle could take refuge. So widespread was the practice of cattle rustling as a tactic of warfare that the plat of our national epic, Táin Bó Cúailnge, centres around a cattle raid. For this reason, Irish raths have much lower profiles than Norman mottes. The defensive trenches are broader and shallower, so that cattle can cross them, and the central mound is lower and of greater area, with grass for grazing.

Despite Orpen’s cogent arguments, the identification of Ballyknockan Moat with Dind Ríg continued to be accepted by many scholars. In 1985 the Irish archaeologist Conleth Manning reiterated Orpen’s criticisms in a short paper published in the Old Kilkenny Review. Manning concluded:

O’Connor’s [recte O’Conor’s] identification has to be rejected because the name does not survive in any form and no trace of a prehistoric or Early Historic monument is at present in evidence at the site. It is of course possible that the motte here was erected on top of a pre-existing monument as happened in cases such as Knowth, Co. Meath, and Rathmullan, Co. Down, but only with archaeological excavation could this be solved one way or the other. In the meantime the motte at Ballyknockan should not be identified unequivocally as Dinn Ríg and should certainly not be described as a hillfort or ringfort. ―Manning 187

In his Onomasticon goedelicum, Edmund Hogan accepted the common identification with Ballyknockan Moat and recorded another of its many names:

dinn ríg ; Dind Ríg ... one of the two palaces of the Leinster kings ... Tuaimm Tenbad in Mag Ailbe ; in tl. of Ballyknocan, ¼ mile to S. of Leighlin Bridge ... ós Berba [overlooking the Barrow], the fort and meeting place of the soldiers of Lein. ... dún ós Berba ... al. Duma Sláinge on the Barrow, betw. Carl. and Lethglenn ... al. Duṁa-Slainge, now Burgage moat, t. Ballyknockan, S. of Leighlinbridge, on W. bank of the Barrow ... ós Berba ... “the most ancient palace of the kings of Leinster,” O’D[onovan]; “situated in tl. Ballyknockan, S. of Leighlin Bridge, on the W. of the Barrow,” O’D.; “a moat measuring 237 yds. in circumf. at base, at a height of 69 ft. above the level of the river, and 45 yds. in diam. at top” ... in Mag n-Ailbe ... ―Hogan 345

T F O’Rahilly, in a footnote in his Early Irish History and Mythology, writes:

Tuaimm Tenba(th) was understood to be the old name of Dind Ríg. ―O’Rahilly 105 fn. 5

Tuaim often occurs in Irish place names. Dinneen defines it as a fortified hill or vallum, and explicitly equates it with dionn (Dinneen )1262.

While the identification of Dind Ríg with Ballyknockan Moat has been questioned, no alternative sites have ever been identified to my knowledge. I believe we can change that. Summarizing what we have learnt so far: Dind Ríg

- was a royal seat

- lay to the west of the Barrow, and close to the river

- was between Carlow and Old Leighlin

- was also known as Duma Sláinge and Tuaimm Tenbad

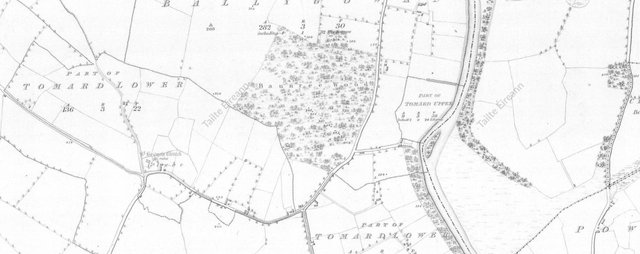

Between Carlow and Old Leighlin, on the western side of the Barrow, there are townlands called Tomard Upper, Tomard Lower and Tomnaslough. Is it possible that the first syllable of these toponyms preserves a part of the old names of Dind Ríg, Duma Sláinge and Tuaimm Tenbath? On Logainm.ie Tomard is interpreted to mean Tuaim árd or “high fortified hill”.

Just to the north of Tomard itself, in the neighbouring townland of Ballygowan, there appear to be the remains of a circular rath. On the Ordnance Survey map this area is called Baunree Wood, which Anglicizes the Irish Badún Ríg, or Bawn of Kings (Quin 62).

A bawn was a ramparted enclosure, where cattle could be secured in time of war. In his Ordnance Survey Letters on County Carlow, O’Conor does actually mention Dinn Righ in connection with these townlands and the neighbouring townland of Rathornan, though he fails to make the connection with Baunree:

... Tomard Lower (Tom nó tuaim ard ... Rathornan [townland] – two raths there, and a moat locally so called, 102-3-4 – of the name of the [townland], 103-4 – Dinn Righ, its existence in this locality not decided ... ―O’Conor (Tullowcreen in the Index)

Rathornan is the Irish Rath Thornáin, which translates as The Rath of the Heap (Dinneen 1235).

Baunree is never mentioned in O’Conor or O’Donovan’s Ordnance Survey letters to Larcom. Baunree Wood is clearly marked on the Ordnance Survey’s 6-inch map, but there is no indication of any ancient raths or earthworks in the vicinity. The nature of the site is only indicated by the addition of tree symbols. Nor does Brindley & Kilfeather’s Archaeological Inventory of County Carlow identify any archaeological sites in this area. The satellite images on Google Maps and Bing Maps, however, clearly show the circular outline characteristic of ancient Irish raths:

The diameter of the structure is approximately 200 m, which makes it almost three times as large as Ballyknockan Moat and comparable in size to Navan Fort. In September 2024 I paid a visit to the site to see what it looked like from the ground. To my unpractised eye it gave every appearance of being a bawn of some significance, with clear signs that it comprised the remains of a multivallate rath. The large field in which it stands did not have any cattle in it at the time of my visit, but there were fresh cowpats at the centre of the structure, proving that cattle had no difficulty crossing the ramparts. From the summit, it commands an impressive view of the surrounding countryside:

Ptolemy’s Dounon

In his Geography Claudius Ptolemy records a list of seven “inland cities” in Ireland. One of these, Δουνον or Dunon (usually Latinized as Dunum), has been identified with Dind Ríg by a number of scholars, though there has never been a scholarly consensus on the matter. As early as 1766 the Irish historian Charles O’Conor of Belanagare listed Dinree as one of the noted places in Munster in Ptolemy’s time. This probably refers to Dind Ríg, which is now in Leinster. The River Barrow once formed the western border of Leinster. In O’Conor’s accompanying map Dind Ríg is called Din-roy and is placed to the east of the Barrow.

The Irish antiquarian Goddard Orpen was one of the first scholars in the modern era to identify Ptolemy’s Dunum with Dind Ríg. In 1916 he revised his opinion and opted instead for Rathgall, an ancient hillfort in County Wicklow. But in an earlier paper from 1894 he had identified it with Dind Ríg and suggested that it was the principal seat of one of Ptolemy’s sixteen Irish tribes:

I should be inclined to place the Coriondi a little more inland, and perhaps we might regard Δουνον as representing their chief seat. This name probably represents the Celtic dún, a fort. What particular dún it refers to, it is perhaps vain to inquire. It might from its position be the famous Dinn Righ on the Barrow below Leighlin Bridge. The form Dunion, which Ptolemy gives as a town of the Durotriges in the modern Dorsetshire, Professor Rhys regards as more Goidelic than Dunon, which would be the Gallo-Brythonic form. If we can rely upon such minute variations of spelling, this would point to the possibility of the Coriondi, like their neighbours the Brigantes, being a Brythonic people. ―Orpen 1894:125

More than half a century later, the Irish Celticist T. F. O’Rahilly revived this theory:

If conjecture is permissible, I would equate [Dunum] rather with Dind Ríg, on the Barrow, near Leighlinbridge, which in point of situation would suit Ptolemy’s data better than Rathgall. As its name, ‘fortress of kings’, suggests, it was once an important royal seat; and from the legend of Labraid Loingsech we infer that it had been such in pre-Laginian times, and that it was captured and sacked by the Laginian invaders. Possibly the Lagin themselves may have occupied it for a time; but there is no evidence to show that it ever was a royal residence within the Christian period. ―O’Rahilly 13

Less than half a kilometer to the west of Baunree Wood lies St Brigid’s Graveyard, an ancient burial ground of uncertain age. It is well known that Brigid was a goddess of pre-Christian Ireland. Goddard Orpen surmised that her name was related to that of the Brigantes (Orpen 1894:123). The presence of her name close to Baunree Wood may reflect the fact that Dind Ríg was originally the royal seat of the Brigantes, who were placed in the southeast of the country by Claudius Ptolemy.

Bibliography##

- Anna Brindley & Annaba Kilfeather, Archaeological Inventory of County Carlow, The Stationery Office, The Government of Ireland, Dublin (1993)

- Patrick S. Dinneen, Foclóir Gaeḋilge agus Béarla : An Irish-English Dictionary, New Edition, Revised and Greatly Enlarged, Irish Texts Society, Dublin (1996)

- Edmund Hogan, Onomasticon goedelicum: Locorum et tribuum Hiberniae et Scotiae, Four Courts Press, Dublin (1910)

- Geoffrey Keating, David Comyn & Patrick S. Dinneen, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn : The History of Ireland, In Four Volumes, Irish Texts Society, Volumes 4, 8, 9, 15, David Nutt, London (1902, 1908, 1908, 1914)

- Conleth Manning, A Note on Dinn Ríg, Old Kilkenny Review, Pages 187–188, Kilkenny Archaeological Society, Kilkenny (1985)

- Thomas O’Conor, Ordnance Survey of Ireland: Letters, Carlow, 14B 14/15, 30 June 1839, Unpublished, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1839)

- John O’Donovan (editor & translator), Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, Second edition, Volume 1, Hadges, Smith, and Co, Dublin (1856)

- Roderick O’Flaherty (author) & James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Volumes 1–2, W M’Kenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Europe, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume IV, Fifth Series, Pages 115–128, Ponsonby & Weldrick, Dublin (1894)

- Goddard H. Orpen, Motes and Norman Castles in Ireland, The English Historical Review, Volume 22, Issue 86, 1 April 1907, pp. 228–254, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1907)

- E. G. Quin (editor), Dictionary of the Irish Language, Compact Edition, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1998)

Image Credits

- Baunree Wood (Google Maps): Google Maps, Imagery © Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map Data © Google, Fair Use

- Baunree Wood (Bing Maps): Bing Maps, Microsoft, © TomTom, © OpenStreetMap Users, © Vexcel Imaging, Fair Use