A Memorial Day Or Disposable Patriotism

Disposable Patriotism: The Paper Plate Republic

A Memorial Day Reflection on Mourning, Memory, and Meaning

Another Day of Flags and Fireworks?

Memorial Day — a day once set aside for solemn remembrance — has become another opportunity for patriotic branding and barbecue sales.

Flag napkins and plastic tablecloths are mass-produced in Chinese sweatshops. Paper plates painted like Old Glory are tossed in the garbage while the sacred Flag Code is openly violated by those who claim to honor it.

All while politicians praise “sacrifice,” and the nation forgets who started this day — and why.

But beneath the shallow slogans and retail discounts lies a legacy written in tears, ashes, and broken bodies. And it began not in Washington, but in the South, among the widows of the Confederacy, walking the ruined fields of a war they didn’t really start — but could not escape.

Memorial Day: A Legacy Rooted in Reconciliation and Remembrance

Origins in the South

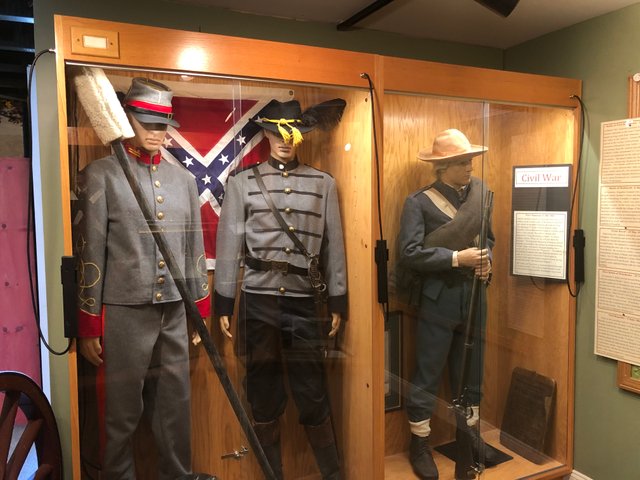

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the South was devastated — physically, economically, and spiritually. With over 260,000 Confederate soldiers dead, it was often Southern women who took up the burden of remembrance.

They formed Ladies’ Memorial Associations (LMAs) across the South — in Richmond, Charleston, Atlanta, and small towns alike — organizing efforts to locate, exhume, and properly bury the remains of Confederate soldiers left rotting in fields and ditches, many still in the uniforms in which they fell.

They did more than bury their own. In places like Columbus, Mississippi (April 25, 1866), these women decorated the graves of both Union and Confederate soldiers, refusing to let even their enemies be left for the crows. This act of grace inspired the famous poem “The Blue and the Gray” by Francis Miles Finch — and helped lay the foundation for a national day of remembrance.

These women understood something we’ve forgotten:

Burial is not about politics — it is about dignity.

Biblical Foundations for Burial and Honor

Throughout Scripture, the burial of the dead is treated not as a formality — but as a sacred obligation.

- Abraham purchased a tomb for Sarah in Machpelah (Genesis 23)

- Joseph asked that his bones be carried to Canaan (Genesis 50:24–26)

- Joseph of Arimathaea buried Jesus in his own tomb (Luke 23:50–53)

- Jesus fulfilled prophecy by being buried with the rich (Isaiah 53:9)

Burial is not just about death. It is a declaration of the worth of the person — and a hope beyond the grave.

So when the South buried her dead, and even Union boys with them, she was living out a truth as old as Abraham and as sacred as the tomb of Christ.

General John A. Logan’s Proclamation

Moved by these acts of compassion, General John A. Logan, Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, issued General Order No. 11 on May 5, 1868, designating May 30 as a day of remembrance.

“The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion… We are organized, comrades, as our regulations tell us, for the purpose… of preserving and strengthening those kind and fraternal feelings which have bound together the soldiers, sailors, and marines who united to suppress the late rebellion.”

Let no neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten… Let us then, at the time appointed, gather around their sacred remains… and garland the passionless mounds above them with the choicest flowers of springtime.”

Logan openly credited the Southern women for inspiring the tradition, stating that they had honored their dead with such grace and consistency that the North ought to do the same.

The Aftermath of Gettysburg: Who Was Buried, and Who Wasn’t

The Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863) left over 50,000 casualties. The Union quickly established the Gettysburg National Cemetery — consecrated by Abraham Lincoln — to bury Union dead.

But the Confederate dead were left behind, buried in shallow trenches, many unmarked and unhonored.

It was not until the 1870s that Ladies’ Memorial Associations and Southern families exhumed thousands of Confederate remains, reinterring them in cemeteries across the South. Their bodies were claimed not by the government, but by grieving mothers and daughters with shovels and wagons.

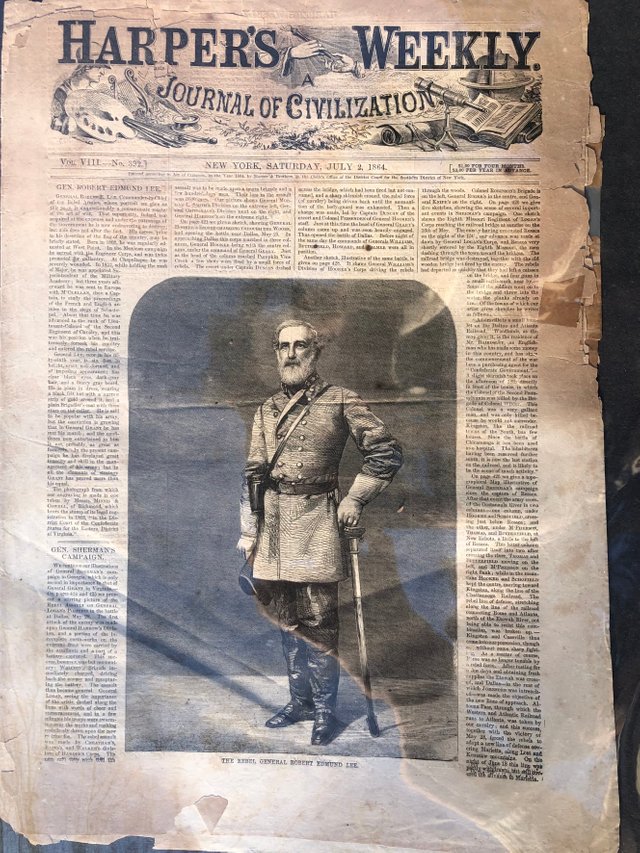

Arlington Cemetery: A Graveyard Chosen for Vengeance

Arlington National Cemetery sits on the grounds of the Lee family estate — the home of Mary Anna Custis Lee and her husband, Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

The Union government seized the property during the war and began burying soldiers in Lee’s front yard, intentionally desecrating the estate so it could never be lived in again.

Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, a staunch Unionist who hated Lee, ordered burials to take place close to the house, including the rose garden and front steps. His goal: to turn Lee's home into a monument to Union dominance.

After the war, Lee’s son, George Washington Custis Lee, sued the government. In United States v. Lee (1882), the Supreme Court ruled that the seizure was unconstitutional and awarded the family $150,000 in compensation — a large sum at the time.

A Pool, a Fence, and the Weight of Memory

When I was small, Memorial Day wasn’t about slogans.

It was when my grandfather — a World War II veteran of the South Pacific — opened the swimming pool he built for his grandchildren.

Not for his own kids. Not for prestige. He and his sons dug it by hand. Poured concrete to the fence.

Every grandchild’s hands and feet pressed into the concrete, with names scratched beside.

Each Memorial Day, we’d measure our hands. Mine got bigger every year. And every year, I wondered when mine would match his.

He died when I was 13.

But I remember that pool — 15 by 30 feet. Rubber liner. Diving board. One ladder. A yellow-painted walkway, sloped so water would run off.

And in the pool shed — a 30-gallon vat of chlorine powder. He told us: “Don’t let even one drop of water touch it. It’ll explode.”

And we believed him. Because he never lied. Maybe exaggerated — but never lied.

He flew an American flag out front. He wasn’t flashy.

If you asked about the war, he’d tell you just enough. Kamikazes. Torpedoes that missed because the ship wasn’t loaded.

He didn’t talk about gore. But he didn’t glamorize it either. He carried it in his eyes.

Later I learned more — from my uncle. My grandfather had told him about a day on deck, behind an anti-aircraft gun, watching a speck on the horizon get larger. A Japanese plane. Straight at them.

They were using their planes as missiles. And one man was torn apart in front of him — but there wasn’t time. He pulled the body from the seat, grabbed the blood-slick handles, and fired until the wreckage passed by.

He didn’t brag about it. Didn’t seek medals. He just built a pool. Laid down concrete. And let his grandkids compare hands every year.

And There Were Others

His brothers-in-law? Five brothers — all in Europe. Battle of the Bulge. Liberators of camps. They all came home. But not all whole.

Uncle Jack came back with shrapnel in his head. Good at first — handsome, strong. But a routine VA check dislodged the metal. Touched the wrong place in his brain. He spent the rest of his life in a mental institution.

I never met him in person. But I talked to him on the phone. He sounded normal.

My mother told me of a day when she went with my grandmother to Marlboro hospital to visit Uncle Jack. She was warned that Jack did not seem to have a problem — however, he did. My mom told me years later how good looking he was and how normal he seemed while they sat out in the yard at a picnic table.

My grandmother excused herself to go inside for some reason and left my mother alone with Uncle Jack for a few minutes. And that’s when Jack leaned over to whisper to my mom that the squirrels were Black people, and they were spies — but not to tell his sister because it would only upset her.

That’s when I understood. He didn’t leave the war. The war stayed in him.

What Memorial Day Meant — And What We’ve Made of It

None of these men talked much about killing, though I know they did. None of them wanted to be remembered with slogans. They wanted their friends remembered.

Memorial Day wasn’t political. It was sacred. It wasn’t about what party you voted for — it was about what your soul still carried.

- Disposable flags.

- Discounts at chain stores.

- Barbecues on flag napkins made in countries that hate us.

But back then? A flag flew because someone bled for it, and the pool opened not for luxury, but for legacy.

Final Words

I suppose in some way I do carry a small portion of the weight they carried — though certainly not the scars. I suppose we all should.

And maybe that’s what Memorial Day should still be:Not a celebration,