“Our Family’s Front Row Seat to History”

Why I Am No Longer a Redskins Fan

This isn’t just a story about a football team that changed its name. It’s a family ledger—inked in a grandmother’s ticket stub at Griffith Stadium, a mother’s quiet walk across the USS Arizona Memorial, and the small loyalties and vows that shaped what we drove, what we bought, and how we cheered. It’s a braid of memory and history—how a Sunday game in Washington and a Sunday attack in Hawaii collided in our blood—and why, in the end, I can’t root for a team that no longer remembers the very story that made us fans.

Most of what I know about that day came from my mother, who told the story again and again—so often I could almost hear her voice before she spoke the first word. She had it down to a rhythm, like a favorite old story that never wore out. My grandmother, Nana, confirmed it when I asked, though she told it more briefly, almost matter-of-fact, like she was handing over a photograph for me to see. My Pop, on the other hand—a man of few words—shrugged when I brought it up. I think he said something like, “Had to work that day,” or maybe, “I went hunting.” He wasn’t one to travel for the sake of it. But Nana certainly was.

Before my mother was born, Nana owned a women’s clothing shop in Red Bank called Addison’s. She had gotten it from a man named Mr. Carol, who had run a small chain of women’s clothing stores. When he went out of business, she took over one of his locations and made it her own. She drove From Downtown lLakewood to Downtown Redbank everyday.. back in 1930s and 40s . She had a sharp business mind and wasn’t afraid to travel wherever she needed to go to get the right goods or meet the right people—New York, Washington, even further if necessary. I’ve got a photograph somewhere of her in Atlantic City, seated at a table with a crowd of people that included Jersey Joe Walcott, the boxer, and several other famous fighters of the day. That was Nana—always connected, always moving. So when she had business in Washington, she went. And that’s how she happened to be at Griffith Stadium on the day history turned.

So growing up I also was a Redskins Fan! Sometimes folks still ask me, usually during football season, if I’m still a Washington Redskins fan. My answer today is simple: I’m not anymore.

Now this is NOT because I stopped caring about football, which I still enjoy watching, but because there are no Washington Redskins anymore. The name’s gone, the history’s been repackaged, and the thread that tied my family to that team was cut without ceremony.

When I was growing up, and in my family, we never saw the name as an insult. We were taught that the name came from tribal leaders themselves, who described their bravest warriors as “Redskins.”

The emblem on the helmet was meant as honor, not mockery—courage, loyalty, strength.

We saw it standing alongside other national symbols of Native warriors—even on coins like the Indian Head nickel and old gold pieces—a reminder of bravery and triumph. That spirit is what my mother and grandmother saw in the team.

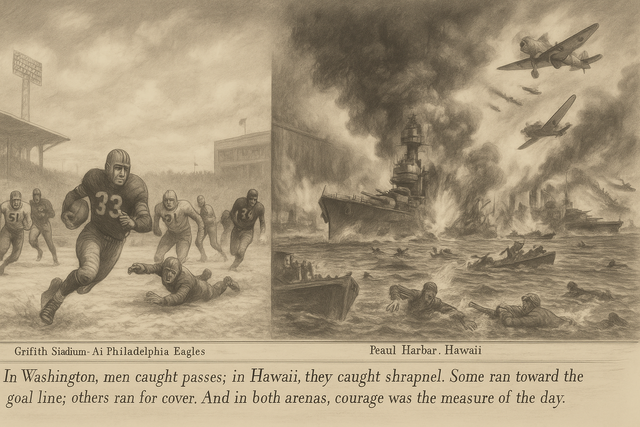

My mother was a Redskins fan. So was her mother—my grandmother, Nana. And the origin of that devotion traces back to a cold December day in 1941, to Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., when the Redskins were playing the Philadelphia Eagles. The date was December 7, 1941—a date that, as President Roosevelt would declare the next day, would live in infamy.

Nana was there in the stands, surrounded at first by a full crowd. The Eagles struck early, taking a 7–0 lead. Washington answered before halftime to tie it 7–7—and that’s when the first strange announcement came across the public address system:

“Will all senior military officers in attendance please report to your posts.”

Odd, but not panicked. A few uniforms rose and left. The game went on.

“Will all members of Congress and their staff please report immediately to the Capitol.”

More people slipped away. Cameras packed up. Washington still battled for every yard.

“Will all enlisted men report to your stations immediately.”

This time, rows of uniforms stood and filed out. Nana said she began to feel alone. The crowd thinned until only a small scattering of die-hards remained, and the quiet that fell over the stadium was unlike anything she’d ever experienced. With so many empty seats, she could hear the quarterback calling the plays as clear as if she were in the huddle. Coaches’ shouts cut across the field without the usual wall of noise to swallow them up. Every cheer from the scattered few carried—one voice at a time—bouncing around the cold air like echoes in a canyon. It was strange—almost unsettling—to watch a professional game in a huge stadium where you could hear individual fans, the snap count, and the sideline arguments, all while having no idea the world beyond those gates was already on fire. I could never have imagined such a thing myself—until the Wuhan Flu emptied stadiums in my own lifetime, and games were played in such quiet that they actually piped in recorded crowd noise to cardboard people in the seats.

Meanwhile, the Eagles nudged ahead again after halftime, 14–7. By the fourth quarter, Washington clawed back—one touchdown to make it 14–13 after a missed point, then another to go up 20–14. There weren’t many left to cheer them on. Nana was one of the few.

Because at that same moment, half a world away in the waters of Pearl Harbor, another game was underway—one with no scoreboard and no cheering section.

The Redskins–Eagles kickoff in Washington was about 2:00 p.m. Eastern. In Hawaii, it was 9:00 a.m.—barely an hour since the first wave of Japanese aircraft had struck at 7:55 a.m. The Arizona had already been mortally hit; the Oklahoma was rolling hard to port; black columns of smoke clawed into the blue morning sky.

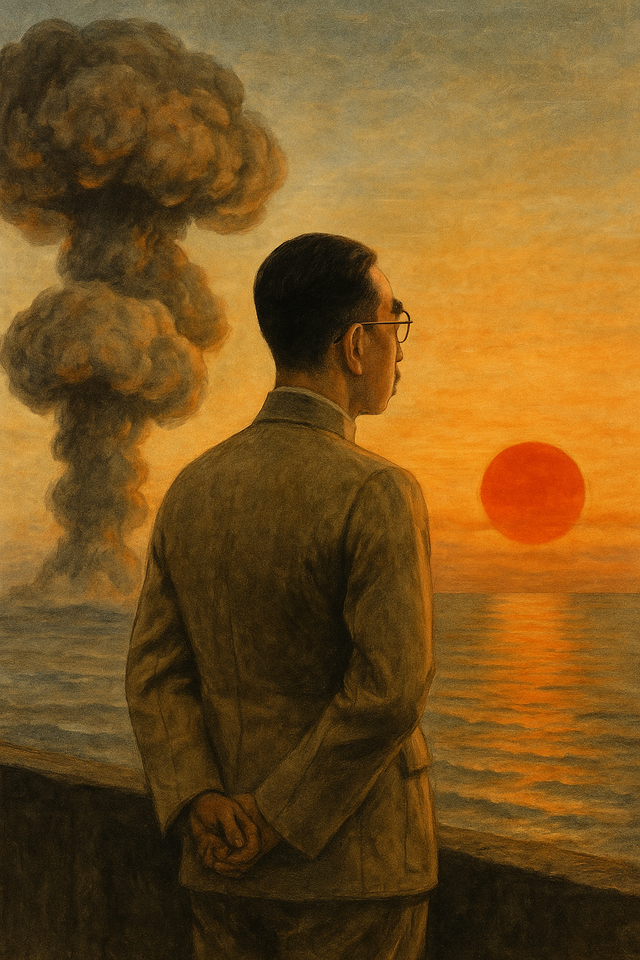

Half a world away again, across the International Date Line, Tokyo lay in the dim stillness of early dawn—just past 4:00 a.m. on December 8 by their calendar. I can picture Emperor Hirohito standing at a window, looking east across the dark Pacific, waiting for HIS sun to rise—more than a national emblem to him, a divine birthright. His admirals already knew their squadrons were over Pearl Harbor. Somewhere in those predawn hours, he must have been waiting for confirmation.

A little over four years later, he would find out that he truly was not God and the son was not his father!

In Washington, the PA called officers to their posts. In Hawaii, sailors sprinted to theirs under a sky alive with gunfire and the scream of diving planes. In D.C., the crowd murmured and thinned; in the harbor, a 1,760-pound armor-piercing bomb plunged into the Arizona’s forward magazine and detonated—splitting the ship, hurling men and steel into the air. In nine minutes she sank with 1,177 souls aboard.

An Eagle receiver leapt high for a catch and tumbled to the turf; sailors on the Oklahoma leapt from a listing deck into oil-slicked water as torpedoes—hit after hit—rolled her finally upside down, trapping hundreds inside darkness and steel. A Washington runner fought for extra yardage; in Hawaii, men fought for fire hoses on the California and West Virginia, trying to hold back walls of flame.

On one side of the world, cheers rose with each first down; on the other, shouts for medics pierced the roar of engines and explosions. Some in Washington caught footballs; others in Hawaii caught hot shards of shrapnel. Some ran toward the goal line; others ran for cover. In both places, men were measured the same way—in courage under pressure, in loyalty to their team or their ship, in the will to keep fighting when everything was coming apart.

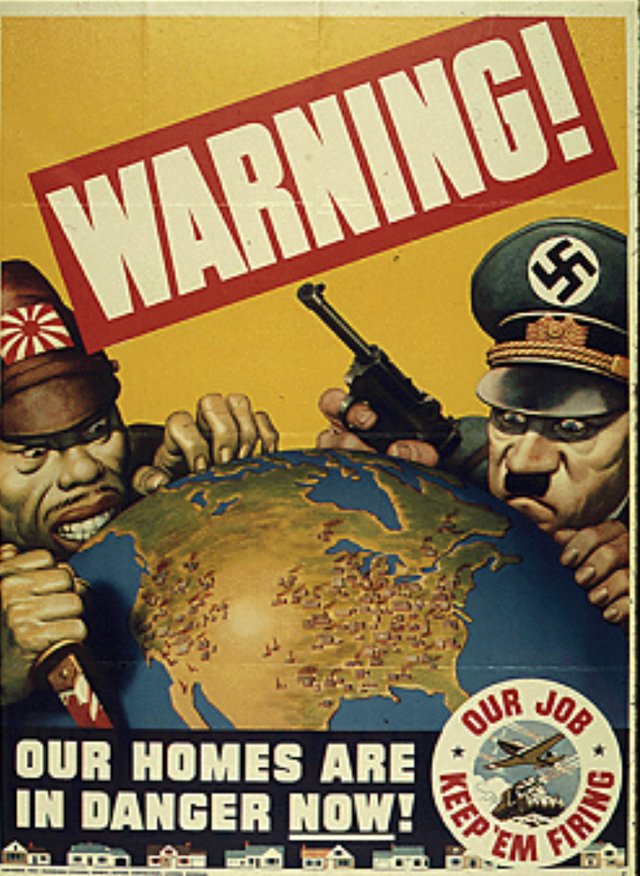

Pearl Harbor wasn’t just a story in the paper for my father’s family—it was a call that changed everything. His father shipped out to the South Pacific with the Merchant Marines, riding dangerous waters to keep the fight supplied. His mother’s brothers went into Europe, fighting across the continent through mud, snow, and blood. They all came home; none came home the same.

In those days, Hirohito and his admirals were as real an enemy to our family as the Philadelphia Eagles were to the Redskins on that field—a rivalry played for keeps, with no off-season. And we all understood the difference: a football game is not a war. No scoreboard can tally what men paid at Pearl Harbor or across Europe. But in the heat of the moment—in the hearts of those playing and those watching—both can feel like the whole world depends on the outcome.

When the war ended, my grandparents swore they would never buy anything made in Japan. For decades they kept that promise. The cars in the driveway were American. The refrigerator, the washer, the stove—American. Even in the kitchen drawers, “Made in USA” was stamped on most everything. Time has its way with vows. My mother was the first to break it—buying a Honda Prelude around 1979 or 1980. My grandfather, who had once braved the Pacific in the Merchant Marines, eventually bought himself a small Honda 250 motorcycle. Nana never gave in on cars or big-ticket items—but I remember finding a little Japanese transistor radio in the house once, proof that even the strongest walls let something small slip through.

Years later, my mother told me about going to Hawaii for a nurses’ convention. She made a point to take the boat to the USS Arizona Memorial. An elderly Japanese man and his wife, well dressed, sat nearby. As they neared the white memorial over the sunken battleship, she saw a tear in his eye. She leaned to her friend next to her and whispered, “He’s been here before.”

They stepped off together and crossed that hallowed place in silence. At first Mom said she was kind of mad at him, but as she watched him She never spoke to him and her heart softened as she saw and felt his remorse. I think she carried both the memory of that man’s sorrow and her own unshakable patriotism and even the bond to the team she’d loved since girlhood. I can almost hear her, as she walked the span above the Arizona,

, Go Redskins.

My mother died just before the team she loved abandoned ship, so to speak. But that day in Hawaii—standing over the resting place of the men who died while her mother watched a game in Washington—her heart carried both loyalties: one to her country, and one to her team.

Go Redskins.

God bless the USA.

And The game has been called “most forgotten football game”

Not by me , even though I was only there by my Grandmother’s eyes and my Mother’s faithful tribute.