Noise-Engine Conversations

(cross-posted from my Substack)

Noise-Engine Conversations

How does “is a hot dog a sandwich?” work?

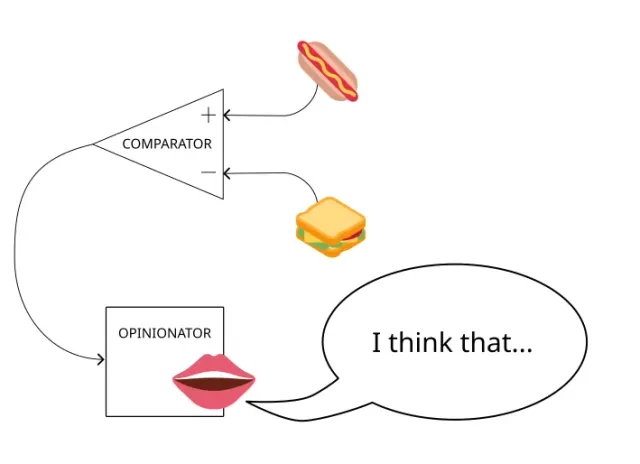

There are types of conversation wherein someone proposes a seemingly-simple topic that somewhat reliably generate an engaged conversation in a group, the best example is probably whether a hot dog is a sandwich. What’s the mechanism that makes this kind of conversation go? I think it works like this:

Initially the topic seems straightforward: you know what hot dogs are, you know what sandwiches are, you merely need to see how well the object fits into the category and report your opinion. Generally there won’t be a good fit, so either “yes” or “no” will seem like plausible answers.

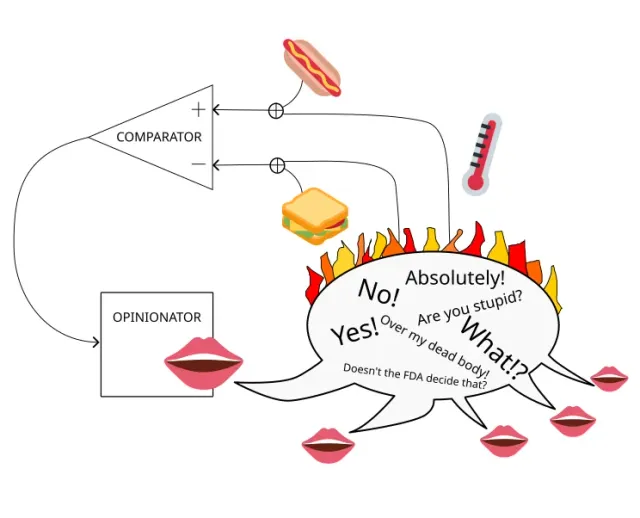

But since there’s generally not only one person giving an answer, the discussion won’t tend to end there. Someone else may disagree, or want to engage in some Socratic probing or devil’s advocacy. Even if answering the question initially seemed straightforward, the analysis will tend to look a lot murkier once a back-and-forth starts. When dealing with electrical devices, engineers have to keep in mind the issue of thermal noise, the fact that heat energy in the components will contribute small random fluctuations to the electrical signals. I think something similar[1] is happening with the hot dog conversation. The heat of the discussion introduces uncertainty into both your perception of the sandwich category and the relevant properties of hot dogs, which may change your opinion about how well they fit the category, which will tend to cause you to contribute your updated thoughts to the discussion, which will keep things going and may cause others to change their opinions, etc.

A whirligig economy?

Like a whirligig, I think a lot of the apparent motion comes not from intense force but by directing most of the force that is there to moving lightweight, disconnected parts. Wind power can be used for things, but if you want to use it to actually saw wood rather than creating the appearance of sawing wood you need big blades and real wind to capture an appreciable amount of energy, not just any passing breeze. The forced dichotomization of whether the hot dog is or is not a sandwich translates minor shifts in perception to bigger shifts in expressed opinion. If the topic was “on a scale from 1 to 10, rate how sandwich-y a hot dog is” you’d likely get a lot less action in the conversation.

Image from the Smithsonian American Art Museum

For the most part it doesn’t matter whether a hot dog is a sandwich or not. Nothing turns on who you think the GOAT of a given sport is. Whether or not something is a “perfect album” or a “perfect movie” has no impact on the world. Not being connected to any appreciable load is a part of what makes this machine work – the random jiggling likely wouldn’t be enough to impact categories that actually have consequences.

Friendly games

This pattern seems like it’s functionally the same as in a “friendly game” of a sport. Most sports are structured as achievement-based tests of athleticism, and in organized tournaments they do work that way: we consider an Olympic gold medalist to have achieved something that meaningfully communicates their prowess as an athlete. But many people use these same games informally, such as playing a friendly game of tennis. It seems like the main factor is that the participants need to be matched in ability closely enough that the vagaries of chance (wind, odd bounces of a ball, etc.) are enough to keep any player from feeling a permanent advantage.

Conversational Junk Food?

With something like a casually-played sport you get the benefits of exercise and spending time with people in an enjoyable activity even if there’s no long-term consequence of the game. In terms of conversations, I suspect that a structure that encourages high quantity but little long-term impact will ultimately feel somewhat empty, even if it seems satisfying in the moment. It wouldn’t surprise me if some arguments in conventional philosophy map to this same pattern – uncheckable factors like what some now-deceased philosopher “really meant” or ambiguities like whether a term is being used in a jargon-y or ordinary language sense may provide some of the necessary flexibility to keep the engine running. The vibes-based “win the news cycle” style of contemporary politics may have some of the same features.

[1] When dealing with some of these information-theory topics it’s not always clear to me where on the spectrum the covers analogies, metaphors, and “literally the same thing” that an idea belongs.