Why Do Some Snakes Have Inexplicably Potent Venom?

Some snakes are incredibly venomous. Whether or not you have a strong background in animal sciences, you've probably heard this fact (or at least one very similar to it):

A single bite from a taipan snake contains enough venom to kill 250,000 mice. Source

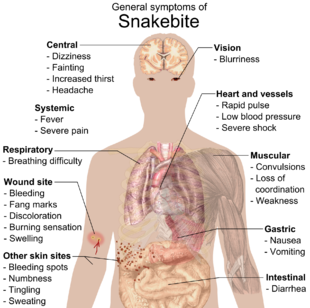

And it's not just snakes that produce these massively potent toxins. A single drop of venom from the cone snail can kill 20 healthy adult humans. Scorpions and jellyfish can kill a person in just minutes following envenomation.

This raises an important question about these animals: why possess a toxin powerful enough to kill dozens (or even hundreds or thousands) if you are only going to use it in one-on-one situations? And considering the fact that these species are not developing their venom with the intention of hurting anything as large as a human, why do they produce such potent cocktails to go after small prey? Source

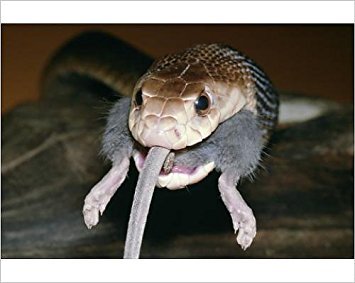

The photo above shows a taipan eating a mouse. Venom is energetically expensive to produce; as expected, more potent venoms require a greater energy input. If the snake is only able to eat a mouse or two at a time, why is it wasting a ton of energy producing a venom that could kill 250,000? At first glance, this doesn't make evolutionary sense. The snake could save a ton of energy by only producing a weak venom that is able to kill its prey. By the traditional view of natural selection, we would expect to see energy-expensive traits disappear unless they were completely necessary, so what reason do these animals have to retain their potency?

One theory suggests that the increased toxicity is evolution's way of compensating for other limiting traits. Think about scorpions for a moment; it's not the big scary ones you really need to be worried about (the venom of the Emperor Scorpion is relatively weak, only about as potent as the sting of a honeybee), but rather the tiny ones like the deathstalker (considered to be the world's most venomous scorpion). If a predator is small, weak or slow, it needs to be capable of taking down prey without it escaping or retaliating. This could easily explain why the higher toxicity would be selected for.

"Box jellyfish are another good example. They are very fragile, and something as muscular as a fish could cause them to rupture from the inside when they [the jellyfish] try to eat it. So venom has to be 100% efficient and cause death very rapidly." - Yehu Moran, researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Source

Some researchers have theorized that economics might play an important role as well. The highly venomous taipan lives in arid deserts, and food can be quite scarce. Since every opportunity for food is crucial, the snake cannot afford to let any prey escape, so it develops a potent toxin that kills quickly. However, many still point out that even in such a circumstance, being able to kill 250,000 mice with a single bite seems largely unnecessary.

Wolfgang Wuster, a venom expert from Bangor University, UK, has a simple answer to the debate.

"It's because they don't eat lab mice. Looking at the lethality of venom to those mice is completely irrelevant to what the snake does in the wild." -Wolfgang Wuster Source

We use mice to create a quantifiable standard (in other words, we essentially rank venoms based on their potency in lab mice). This is primarily for the purpose of designing antivenoms in humans.

"The mouse model enables standard data to be acquired, but mammals are not always the diet of preference, so toxicity in mammals is simply a standardised metric that probably has no bearing on toxicity to an amphibian, arthropod or bird." -Robert Harrison, head of the Alistair Reid Venom Research Unit at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK Source

Wuster believes this may be key to answering the question.

"There's no such thing as absolute toxicity. If you want to know how toxic something is, the first thing I'm going to ask is: 'what do you want to kill?'" -Wolfgang Wuster Source

Most venomous animals, snakes included, target a very specific species or group of animals. This chosen prey will shape the evolution of their venom though a series of events that we would call an evolutionary arms race. It probably went something like this:

- Snake (or other venomous species) produces a mild toxin capable to killing/incapacitating prey.

- Prey species develops immunity/resistance to the toxin.

- The predators venom increases in potency to overcome the tolerance.

- The cycle continues as both predator and prey increase toxicity and resistance respectively.

Marvelling at how many mice could be killed by a single snakebite makes about as much sense as being surprised that a cheetah can easily outpace a tortoise. The cheetah simply did not evolve to hunt tortoises, and consequently the tortoise did not evolve to escape cheetahs. Source

"There's a species of mouse in Israel that weighs 20g and can survive a bite from a saw-scaled viper that would have you or me bleeding from every orifice and in intensive care. I would put a fair bit of money on there being one tough mother of a rat in Australia that can survive taipan venom." -Wolfgang Wuster Source

Assuming there is such an animal, it has likely evolved such a resistance because it is the key component of the taipan's diet. It has little to do with size; species such as hedgehogs, ground squirrels and mongooses are resistant to many venoms that could easily kill a healthy adult human. Why? Because we simply did not put much effort into evolving any sort of resistance to venoms. If an animal has developed potent venom to take down highly resistant prey (even as small as mice), it probably has the lethality to kill humans and larger animals.

"Primates just don't seem to be prone to developing venom resistance." -Wolfgang Wuster Source

For now, it makes sense to use lab mice as a standard for snake venoms (like us, they lack the resistance to these venoms), but we need to realize these toxins are not a standardized weapon. Their effects are not universal, but are specially crafted towards certain targets. Snakes are not evil creatures, and they did not design deadly toxins to kill us...unfortunately, we are just poorly equipped to deal with their potent venom.

Also it needs to be mentioned that snakes can adjust the amount of venom used in a bite, sometimes warning bites can be venom-less.

This fact is true, snakes do have control over their venom glands and can adjust their delivery. The only reason I left this out of the article is because, while they can adjust volume, they have no control over their potency. Even if they only deliver a small portion of their venom, the fact remains that this small amount is likely to have a profound effect on any species that has not evolved a resistance to that venom. Overall, I just wanted to explain why the potency is as alarmingly high as it is, regardless of volume per bite.

I never thought about mice developing immunity. That makes a lot of sense. It is not so they can take down bigger and bigger animals. It's the same as the arms race or bitcoin mining. It is simply an after effect of an ongoing struggle for survival between prey and their primary predator.